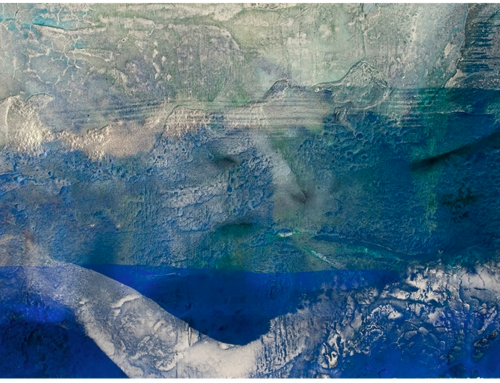

Female Waters is one of the featured exhibitions in the 2019 Jerusalem Biennale. The theme of this years event is ‘For Heaven’s Sake.’ Artist Chani Cohen Zada explores the female experience, and divine encounters, through accounts in scriptures. These works transcend the past and resonate with experiences that still deeply held today. Cohen Zada is a member of the female art collective Studio of Her Own and the Shoshana Gugenheim-funded international project Women of the Book. Her work is held in the Karen Davidson, Shallot, and Shmuel Hayk collections, as well as in private collections in Israel and Australia. As a person of enduring faith, and a mother of seven boys, the artist connects her own experiences to her scholarship of the Talmud and the Torah. She also highlights female figures in these narratives, exploring their identities and God encounters. Further, Female Waters connects the stories of these women to the mystical concept of feminine water, a force that flows toward Heaven as it seeks to be received. Surreal qualities throughout the exhibition express the meeting of Heaven and earth in the stories of these women.

There are many enduring symbols throughout the exhibition. Rocking chairs are symbolic of the force of motherhood, and the acceptance of the childish qualities that still live in us as we age. The color purple is shown in various tones, speaking to the ability to adapt in new situations. “Most of the symbols are personal. People don’t understand what I’m talking about or what I am trying to say, but I actually like that. I like that people find their own commentary in what they are looking at.” One overarching concept is the symbolism of the Tree of Life. This concept in Jewish mysticism greatly influences Cohen Zada in her approach to both art and life. It comes from the book of Genesis, where a tree of life was planted in the Garden of Eden. This motif is featured throughout the book of Proverbs with references to its “fruit of righteousness” (15:4) and “healing tongue” 11:30). “There are ten different emanations and they go one after the other,” she says. “Each one is nearer to God.”

The artist states that she loves both creative expression and the Torah. When prompted to compare and contrasts these loves, she says, “I don’t think they are different at all. I think that painting from observation is something that introduced me to the Tree of Life.” She explains further that there is a quality of mindfulness, wherein one patiently witnesses each step of their spiritual journey and the ways in which they uniquely desire to grow closer to God. Cohen Zada works on one painting for 3 months sometimes, immersed in this spiritual journey.

The Tree of Life is a framework for how Cohen Zada approaches each new work. “The [highest emanation] is wisdom, which is the godliest,” she says. The emanation on the opposite end of the spectrum is the most distant from this state, “it is like being the king of yourself, leading yourself to the world, but that is the farthest away from God.” Starting in this state, one must work through each emanation to reach the state of wisdom and relationship with God. Cohen Zada feels that this is integral to how she creates her art and how she lives.

The artist’s insight comes from not only a study of the Torah but a study of the Rabbinical commentary. These texts unlock the deeper meaning of the scriptures in a way that fascinates the artist. Often, she begins by searching for concepts that she is reflecting on in the Torah. At other times the scriptures themselves provide a vivid image for her, a translation of their meaning in her own creative language.

Cohen Zada inherited the white rocking chair that is featured in many of her paintings. It belonged to her mother who passed away when the artist was 27. As a mother herself, she felt that she lost a source of guidance on her own motherhood journey. It was a loss of both mental and physical help. In her spiritual life the artist would find the “inner motherhood” that she possessed to raise her family.

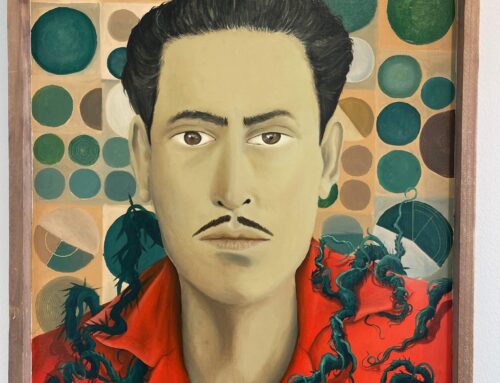

Let Thine Eyes be On the Field (above) is one of the works where the rocking chair motif appears. It is covered in a white prayer shawl that hovers over the back of the chair, suggesting the shape of a head. In the seat is a tiara, symbolizing a child’s desires for attention. The opposing forces of mother and child come together in such a way that “motherhood hugs the child.”

“There is someone sitting there. I tried to capture the soul of the person. This is dedicated to Ruth in the Bible. In Hebrew, it says that she had ‘good eyes.’ It means that when she looked at somebody, she saw what was good in them. It’s like you see a person as a whole. Some people tend to see what’s bad, some people can see, whatever, but some people see the good parts of that person.”

I Will Cover Thee with My Hand (above) features a tiny rocking chair that is embraced by a seemingly animate prayer shawl (tallit). “The tallit symbolizes the presence of God,” she says. The rocking chair represents the children of Israel after they received the Torah, and rebelled by creating a golden calf to worship. “God forgave them, and the word for this in the Torah means a ‘hug’ or ‘covering.’ In this scripture “he told Moses ‘I will cover you while I pass. You can be there, but you can’t see me, and I will give you this hug.’”

Afterbirth (above) further speaks to theme of motherhood, the female experience, and God’s promises to women in scripture. The painting is about Jacob’s wife, Rahel. The little house in the clouds (left) is Rahel’s tomb on the road. “She is watching out for her children. She can’t be comfortable in the tomb with her husband and the rest of the forefathers. She’s waiting for [her children] to come home. The Rabbinical commentary says that, and so does the prophet Jeremiah. That she cried about her children being sent to exile and God told her, ‘I hear you. I hear your crying, and you should know they will come back.’” The title of the work ties back into Rachel’s character. “I called it Afterbirth because of the placenta, the only organ in the world that is only for somebody else. Once the woman gives birth the placenta has no more meaning. The placenta dies. I thought about Rahel being there for somebody else. She didn’t care about herself, she cared about her children.”

Female Waters is currently on view at the Wolfson Museum in Jerusalem until November 28th. Learn more at Chani Cohen Zada, and view her past work and upcoming projects at chanicohenzada.com.