“The Family,” 2016, oil on canvas on panel, 96 1/2 x variable length, Photo by: Ben Bascombe (Valley House Gallery).

Community is at the heart of Sedrick Huckaby’s work. Compassion and connection are integral to the act of art-making. They hold the same importance as the finished product. Bridging the past, and present, and engaging the future are enduring themes in Huckaby’s work. The artist received his MFA in Fine Art from Yale University in 1999. His work is held in several permanent collections, the American Embassy of Nambia, The Whitney Museum of New York, and The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University among others. In 2018, Huckaby was named the Texas State Artist, an honor offered to artists who enrich the cultural landscape through their contribution to the arts. Huckaby revisits elements and objects from the past in ways that renew our perspective and raise new questions. We are offered an opportunity to not only revere the past but communicate with it.

When Old People Talk to Young People is a series of oil paintings of family quilts. These paintings place the quilts in a new context, removing them from the living room sofa or the cedar closet to become objects of contemplation. A quilt holds a legacy. The symbols in the patterns and stitches immortalize our ancestors and act as placeholders for their state of mind. The storied objects on canvas become revered as the voice of one generation speaking to another.

“Quilt for Christ,” 2006-2008, oil on canvas on panel, 108 x 168 in, Photo Courtesy of Valley House Gallery.

“Filthy Rags of Splendor,” 2011, oil on canvas, 108 x 108 in, Photo Courtesy of Valley House Gallery.

The creative process and project orientation of The 99% was quite complex. The act of art-making itself was the height of action, a phase where connection, wonder, and futurist thought collided. The 99% stemmed from curiosity about the current events that are marketed to us, versus the concerns in our communities. Huckaby says, “My whole point was to listen to people and see what was on their minds.” He visited his hometown of Highland Hills, Texas, and began drawing portraits of residents. Beside each portrait, he scrawled their personal concerns on the page. “Art led to listening, to recording, that was a simple gesture.” This humble approach revealed the consciousness of the community, a variety of concerns, hopes, and dreams that ranged from the mundane to the deeply felt. This combination of art and action, art as a medium for the generation of possibility, has intrigued Huckaby throughout his creative journey.

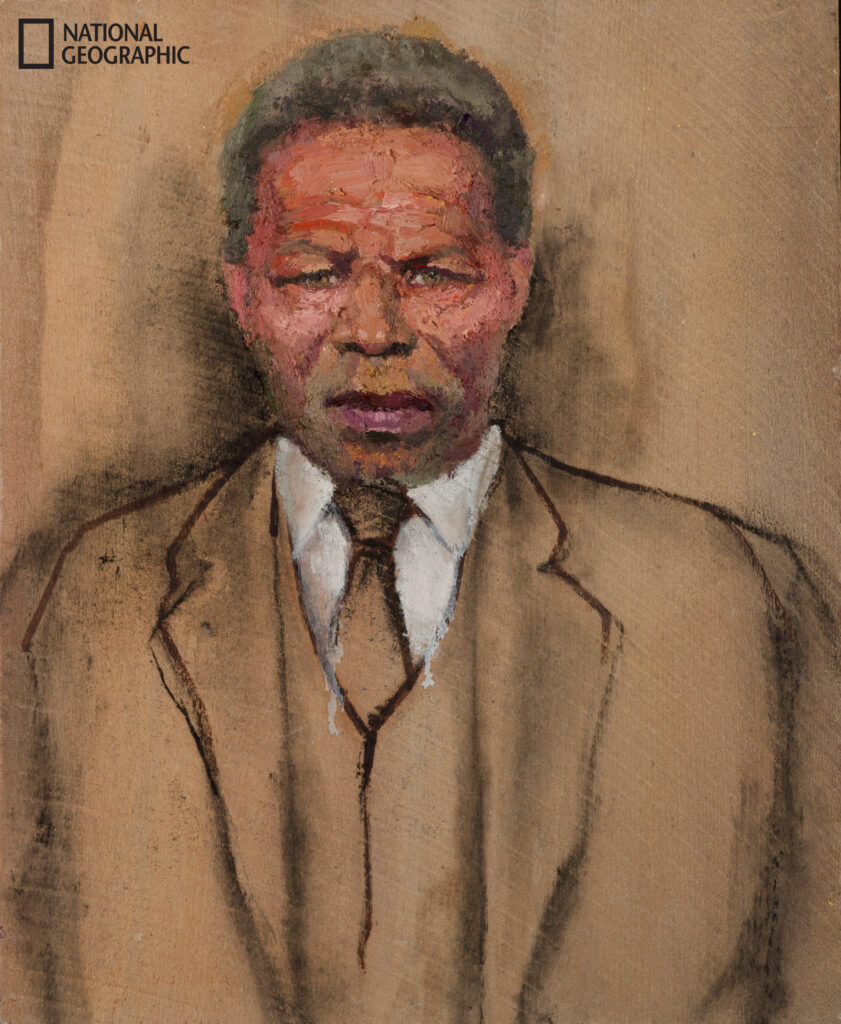

In February of 2020, Huckaby’s work was featured in National Geographic. The artist painted portraits of community members in Africatown, Alabama. The publication ran the feature story The Last Slave Ship on The Clotilda, the last recorded ship to illegally transport Africans to America where they would be enslaved. The ship was unearthed in the Mobile River, a piece of history that had been burned and buried in an effort to erase its legacy over one hundred and fifty years ago. Among the residents of Africatown, North of Mobile, are the descendants of the captives. The Clotilda was in their family history, but the physical ship had never been found. As the residents of Africatown finally met a piece of the past, Huckaby painted their portraits alongside those of their ancestors.

“Charlie Lewis,” 2019, oil on panel. The oldest of the Clotilda captives, Oluale, who took the name Charlie Lewis (pictured in the illustration), settled in an area that became known as Lewis Quarters, where some of his 200-plus descendants still live. Stories about the Clotilda were always taught in our home, says Lorna Gail Woods. ÒAfricatown was a proud place to be raised.(Painting by Sedrick Huckaby) – Feb. 2020, National Geographic

“Little by little I am understanding my interests as an artist,” he says. The concepts that he feels are important, traditional art, life experiences, and faith – “they are bundled together in the art that I’m producing.” The overarching themes of compassion and reverence for community come from the artist’s connecting to others through Biblical roots. He describes his philosophy as beginning with simply loving God and loving one’s neighbor. By expanding that love to a wider community, within that awareness, the ability to recognize God’s presence in our larger reality is possible. We can explore the community from a place of compassion.

Huckaby is married to documentary photographer and fine artist Letitia Huckaby. For them, art is a separate endeavor, but they follow their callings side by side. This unusual pair, as working artists and parents of three children, spark conversation about the role of family and relationship. This comes from the way that they live and the work that they each create. “There is still room for people to be cutting-edge Contemporary, and speaking about the things that are at the heart of our lives,” he says. Community, diversity, and “how we live together is such a complex thing.”

The artist recently returned from a two-week residency in New Delhi, India with Art for Change. In the fall, Huckaby will be the Ruth Mayo Distinguished Visiting Artist at the University of Tulsa in Oklahoma. Learn more about the artist and his upcoming projects at Huckabystudios.com

Visit this link to learn more about “The Last Slave Ship” by