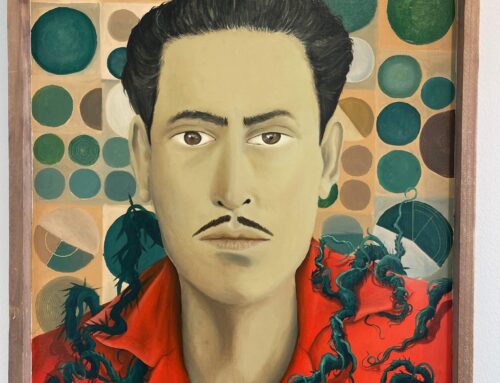

“Black is Beautiful”

Family, culture, and faith are enduring themes in Letitia Huckaby’s art. Her family’s birthplace, the American South, is a tremendous part of her practice. Having grown up abroad in Europe, photography was a bridge for her to connect to her Southern relatives when her family returned to the States. “I was learning more about myself the more that I learned about the place.” Her father retired from the military and the family settled in Oklahoma when Huckaby was a teenager. The artist would spend much time with family in the deep South, eventually documenting their stories.

Huckaby was a dancer from the ages of four to eighteen. Twice, she attended an arts camp in Oklahoma where visiting artists shared their craft with local teens. After high school, she was offered the opportunity to return to the camp to work in the public relations department. That year Christopher James, a documentary photographer and Boston Art Institute professor, exhibited his photographs of a death hotel in India. In the establishment, a place where lower-income people convalesce at the end of their lives, James photographed a man’s last breath. “It was a photo of an old man lying on a cement bed. They had a candle beside him to light the room. You could see the smoke going in one nostril and out the other.” This image impacted Letitia Huckaby greatly. Struck by the power of documentary photography, she would sell her possessions and enroll at the Boston Art Institute to study under James. She remembers working full-time as a stock person at a retail chain, living in an unfamiliar city. She says, “It was a powerful time.” Indeed, it proved to be a formative experience for her as a person and an artist.

After earning her Bachelor’s degree in photography, Huckaby returned to the South, but this time to Texas. She wanted to be close to her extended family. Professionally, she photographed weddings, portraits, and sporting events, among other commissions, to make ends meet. During this time, her artistic practice was continually drawn to the South. “It’s so different from anywhere that I grew up,” she says, “It’s like its own country.” She started researching her ancestry and talking to older relatives about their own personal histories. “It allowed me to honor them,” she says. “They were excited that I was making art about them.”

“Wahaxachie Cotton”

“Quilt #1”

“East Feliciana Altarpiece”

Following her father’s passing, Huckaby became interested in the legacy of his hometown in Mississippi. The state was the fourth-largest producer of cotton. For a person who had enslaved ancestors, cotton holds much meaning in and of itself. The material has a wealth of history connected to it. “I began photographing it like it was precious, like a rose.” Huckaby began printing on fabric, and found that the unusual medium is a universal heirloom that connects people to their own family history and traditions. Fabric has a built-in history of its own. At first, she printed on newly purchased fabrics. After inheriting her great-grandmother’s quilts, dishtowels, and garments, Huckaby began using her own family heirlooms. The fabric and the clothes transcend the role of a canvas. Huckaby’s prints interact with the rich history of textiles, highlighting their stories and creating a dialogue between the past and the present.

Despite feeling at first distant from her Southern roots, Huckaby’s family ties have given her a perspective that doesn’t fall into sensationalizing or stereotyping Southern life. “People who aren’t related to me or my family can see honor, respect, and spirituality in [the images].” Art collectors often draw connections to their own family memories and speak to Huckaby about a spiritual quality that they sense in her work.

At the Tallgrass Artist Residency in the summer of 2019, stories about culture, migration, and dreams inspired Huckaby. The artist researched African American communities that were established in Kansas following the abolition of slavery in 1860. People were promised forested land to build their own houses. Upon arrival, they saw that trees were scarce in the flat region. Some returned to the South. Others stayed and put down roots to become homesteaders. Huckaby was intrigued about this part of history: the promise of beauty, the dream of starting over and creating a life of one’s own. This includes the hardships on the road to achieving that dream. Huckaby researched and visited the town of Nicodemus, where a museum exists today and is run by the descendants of African American homesteaders. The artist began documenting the land and agriculture. She purchased a woman’s work dress from the 1800s on which she printed images of the landscape. The dress acts as a placeholder for the former wearer, a symbol of all the migrants to Nicodemus, and the images that represent their well of hope and desire. “The landscape was what their dreams were about,” she says.

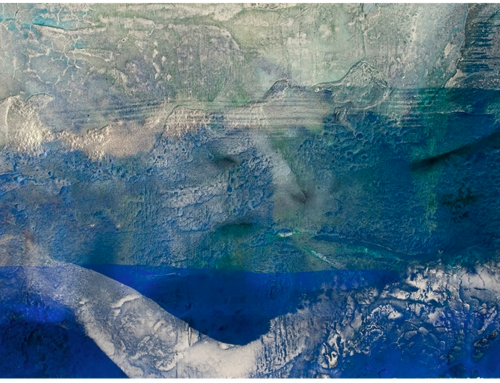

“Black is Blue”

Tallgrass is among the few artist residencies that Huckaby has pursued. Her own loved ones – husband and fellow artist Sedrick Huckaby and their three children – are a major part of her creative rhythm. Both artists balance parenthood and the pursuit of expression by keeping their children close. Their artist’s studios in the Fort Worth, Texas area are adjacent to their children’s playroom.

This fall Huckaby’s work be included in the exhibition 1619/2019 at the Muscarelle Museum of Art in Williamsburg, Virginia. This exhibition features African American and Native American artists exclusively and explores the commemoration of Virginia through a contemporary lens. This also marks the 400-year anniversary of the first documentation of the arrival of slaves in the state. 1619/2019 will be on view from November 6 – January 12, 2020. In the spring, Huckaby will be a featured artist in Houston’s city-wide FotoFest Biennale, on view from March 8 – April 19, 2020.

Learn more about the artist and her upcoming exhibitions at huckabystudios.com

1619/2019

603 Jamestown Road

Williamsburg, Virginia 23185

11/6-1/12/2020

City-wide locations

Houston, Texas

3/8-4/19/2020